The Cartwrights ride into Season Two!

By Paul Mavis

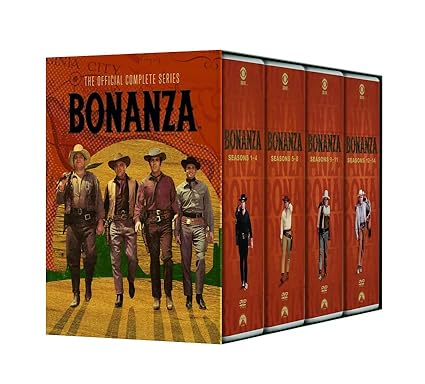

As we continue our months-long (maybe years, even??) look at CBS’s and Paramount’s fabulous DVD boxed set, Bonanza: The Official Complete Series, lovingly and painstakingly restored and remastered under the supervision of TV historian Andrew J. Klyde, the 34 (!) episodes of Bonanza‘s sophomore 1960-1961 season finds the series, which was already confident and brash right out of the gate, further refining the characterizations of the four central leads (Lorne Greene, Pernell Roberts, Dan Blocker, and Michael Landon), while consistently producing strong, layered, and extremely well-constructed one-hour playlets that hold up with the best dramatic anthologies from that time period. As with every season here on this remarkable boxed set, the extras overflow this outing, while those pesky source material problems noted by previous DVD buyers of the second season, have been addressed, with beautifully remastered transfers from the original―and cleaned up―35mm color film camera negatives.

Click to order Bonanza: The Official Complete Series on DVD:

(Paid link. As an Amazon Associate, the website owner earns from qualifying purchases.)

It’s the late 1850s, and gold and silver fever are sweeping through the hills and valleys of the celebrated Comstock Load. Virginia City, Nevada, sitting right on top of those millions of dollars’ worth of ore, is bustling with miners, settlers, businessmen, rustlers, con artists, and killers. And butting right up against Virginia City is the massive Ponderosa ranch, a thousand-square mile New World Eden filled to the brim with pine and beef.

Overseeing this operation is voice-of-God Ben Cartwright (Lorne Greene), the thrice-widowed land baron who watches over his spread as fiercely—and as tenderly—as he does his three grown sons. His eldest, Adam Cartwright (Pernell Roberts), is the most serious of the three siblings, and the one who works most directly under Ben in running the Ponderosa. His mother the daughter of a New England sea captain, Adam was schooled back East as an architect and engineer. Middle son Eric “Hoss” Cartwright (Dan Blocker) gets his massive physique from his mother, a six-foot tall Swede who could punch like a mule. Hoss, who may seem rather dim or naïve at times when he’s not killing a bear with only his hands, or knocking down a tree, is in reality quite sensitive to his surroundings, and to the sufferings of others.

Finally, Little Joe Cartwright (Michael Landon), the youngest son, gets his smoldering dark looks and equally tempestuous nature from his beautiful half-Creole mother, whom Ben met during a trip to New Orleans’ French Quarter. Little Joe is certainly the most reckless of the clan, relying on his charm and his fast fists to both get him into trouble, and out of it again…especially if there’s a lady involved. Constantly patrolling their land to keep opportunists at bay, the Cartwrights inevitably get involved week after week in the troubles of others, who look to the Cartwrights as one of the few stabilizing forces in the wild and woolly excesses of the Old West.

In my season one review of Bonanza, I wrote extensively about the series’ inception, its production, and the aesthetic and thematic framework underpinning the show’s construction. So I won’t cover the same ground here…an unnecessary task, anyway, since the show remains largely unchanged from season one. Themes that were first introduced in the previous season are expanded in this go-around, including the notion that the Cartwrights are somehow different and “special” compared to the average settler or farmer out in the West; that the sheer magnitude of their wealth engenders both awe and envy from outsiders (sometimes negatively coloring that “special” status the Cartwrights enjoy); that violence in the Old West is to be avoided at all costs if civilization is to come (although it remains a necessary evil); that cultures will clash in the forward expansion of the West; and that the Ponderosa itself is an almost mystical source of bounty that must be protected―heady themes all for a television genre that is often dismissed by newer critics as the domain of mere shoot ’em-ups.

In the season opener, Showdown, there’s a funny throwaway about the Cartwrights’ “specialness” that reduces that distinction to their outsized appetites. An amused woman, observing Little Joe’s seduction skills and Hoss’ hunger, states, “You Cartwrights: if it’s not one thing it’s another.” The Ponderosa is the biggest land parcel out there in Nevada, and this moment suggests the men who run it have earthy passions to match that vastness.

However, in episode after episode, the Cartwrights’ moral superiority―carefully couched in populist humility―is shown to be far stronger than their corporeal desires, as well as being the only stabilizing force in this untamed frontier, a civilizing force for good that’s remarkably unselfish when one tallies up the Cartwrights’ forgiving nature in the face of wrongdoing. A good example of this is The Blood Line, written by William Raynor and Myles Wilder, where Ben, after killing a drunken rogue in self defense when the man complains about the “high and mighty” Cartwrights, takes in the dead man’s son and tries to teach him that violence isn’t the answer to life’s tribulations…even though the boy continually vows revenge on Ben’s head, and escapes time and again.

Several times in the story, everyone urges Ben to have the dangerous boy locked up, but Ben refuses; he doesn’t want the boy, well played by David Macklin, to believe that force and violence are the answers to a deeply troubled young man’s problems―a rejection of violence on principle that wasn’t as novel and unique in television westerns as some critics (who haven’t actually watched these old shows) would have you believe. Other good examples of this “violence-only-as-a-last-resort” creed in Bonanza (a creed that certainly sets them apart as “special” in a land of quick draws and cheap death) comes in Badge Without Honor, where Dan Duryea’s perverted love of efficient killing can’t win out over the Cartwrights’ reluctant use of force as a cleansing agent of justice, and in The Hopefuls, where pacifist Patricia Donahue can’t forgive Adam’s necessary use of violence―even though she knows he had no other choice―thereby scuttling their romance.

In Bank Run, written by N.B. Stone, Jr., and directed by none other than Robert Altman, the notion of the Cartwrights’ moral superiority is given a humorous twist when Hoss and Little Joe must rob a bank to save it from its nefarious owner, the marvelous Ian Wolfe. He wants to swindle the investors with an eye on eventually acquiring the Ponderosa―covering another theme discussed below: the notion that the Ponderosa is under constant threat from those who envy what the Cartwrights have carved out for themselves. A more brutal example of the Cartwrights’ almost mandated role as civilizers comes in the effective Cutthroat Junction, where Robert Lansing (a great, great actor who just missed major stardom), as a stage coach troubleshooter, turns bad and takes over a town, with Ben and the boys stirring the locals on to fight Lansing…or live in a constant state of fear. In many episodes, the Cartwrights aid anyone they see as pioneers like themselves; people willing to carve out their own destinies, while delivering justice to those misguided enough to think they can take, without having earned.

Envy and avarice for what the Cartwrights have carved out for themselves also drives many supporting characters’ motivations this season. The best example, The Bride, written by Richard Newman, finds a local sheriff, played by John McIntire, engineering a nifty little scam with Adam West and Suzanne Lloyd to steal away the Ponderosa by setting up Ben for murder. Arriving at the Ponderosa after claiming to have been married to a phony “Ben Cartwright,” Lloyd marvels at the sight of the ranch spread out before her: “Must be wonderful to live on a place like the Ponderosa. A place almost as big as an entire state,” she offers, to which the proud-but-humble humanist Ben replies, “Well, Miss Jennifer, it’s not what a man has that’s important. It’s how he got it, and what he does with it that really counts.” Responding in the best class-warfare manner, Lloyd tentatively parries with, “But how does one man get so much?” to which proud Little Joe responds, in the best―and now sadly flagging―American tradition, “By working till his back’s near broke, like our Pa did.”

Lloyd, continuing on in what could be a dialogue on the woke Congressional floor today, responds, “Other people work hard,” to which sensitive, poetic Hoss replies, “Yeah, but maybe other folks don’t dream like our Pa did, Miss Jennifer.” So much for petulant, unearned jealousy in the face of hard work and capitalism. And just to drive home the point, forceful Adam seals the deal with, “Yeah, and fight to keep it,” signaling that the Cartwrights may indeed help those less fortunate themselves―if they feel they’re worthy―but they’re not giving away anything out of guilt over their success.

Further proof of the Cartwrights’ unflinching willingness to materially aid others only if they’re deemed worthy of the help, comes in the complex Day of Reckoning, written by Leonard Heideman and R. Hamer Norris. Ricardo Montalban is a Bannock Indian shunned by his brother and tribe chief Anthony Caruso for marrying Shoshone Indian Madlyn Rhue. When Caruso tries to kill Ben, Montalban saves him, as much for his Christian wife Rhue’s religious beliefs as for his own conviction that Indians will have to come to terms with living with the White man in peace.

RELATED | More reviews of TV Westerns

In gratitude, Ben offers him a stretch of land that’s adjacent to the Ponderosa…as well as next to a racist farmer. Tormented by his thoughts that he fits neither in the warrior culture of the Indians or the farmer culture of the White settlers, Montalban flips when his wife is killed, going so far as to torture Ben, before he’s transformed by Ben’s still-forgiving nature. It’s an extreme example of Bonanza‘s overriding social and ethical tolerance (as well as another example of 60s television tackling difficult racial issues), and one that stays remarkably consistent and clear throughout the series.

In the excellent The Thunderhead Swindle, written by Gene L. Coon, Ben is distraught over the economic depression sweeping the Comstock. Given the chance to look the other way concerning an adjacent played-out silver mine, Ben rejects the swindle on the town of Virginia City involving a bogus “stimulus plan” that would have had only short-term benefits before destroying the town completely (sound familiar?). Instead, he risks his life (and gets poor Vito Scotti killed in the bargain) to thwart the crooks and set Virginia City back on its feet, with working men getting a day’s pay for a day’s labor. Some modern viewers might cringe at the final, paternalistic sight of wealthy Ben smiling approvingly at the town getting back to work, but then as now: no one ever got a job from a poor man.

As for the Cartwrights themselves, Bonanza‘s writers, in the first half of this second season, seem prepared to stick to the already-established personas, refining the men’s characters to the point where we always know Ben will be forever-patient and paternal and understanding, Hoss will be deceptively simply yet poetic and sensitive, Adam will be mysterious and elegant and perhaps…slightly cynical in his own private thoughts, and Little Joe will laugh his way through women and gunfights. What’s particularly striking, though, as this second season progresses, is the increasing emotional intensity of many of the stories focusing on the individual Cartwrights. It’s as if producer David Dortort knew he had to further flesh out these characters if he was going to move the series forward, and the results are fascinating.

Adam’s cynical, sophisticated character is given a cool showcase in The Fugitive, where he must go down to Mexico and investigate the mysterious death of his old childhood friend, James Best (in his best psycho mode). Not only does Pernell Roberts do well in this Western gumshoe/whodunit framework, but the sticky problem of racism―this time on the part of a Mexican sheriff who distrusts Whites―is tackled, as well, with sensitivity by scripter Richard Landau.

Hoss has not one but two excellent episodes where his character is rounded out. In Vengeance, Hoss, like a Western off-shoot of Lenny in Of Mice and Men, accidentally kills a rowdy drunk (with an unknown heart condition), and spirals down into self-destructive depression, almost willing himself to die from a gunshot wound rather than face his own guilt (hothead Little Joe also learns about flying off the handle, reigning in his killer instincts at the last second). And in the searing The Rival, written by Anthony Lawrence and directed by Robert Altman, Hoss is torn between his love for Peggy Ann Garner, and her request that Hoss save her love, Charles Aidman. It’s a wonderfully sad, mournful episode from Lawrence, giving the normally effusive Dan Blocker a chance to play interior (which he does quite well), directed with grit by Altman (the vigilante hanging sequences are quite strong for 1961 network television).

As for Lorne Greene, Ben gets this season’s most romantic episode, Elizabeth, My Love, again written by Lawrence, where we learn of Ben’s backstory as an Eastern seaboard sailing captain, and his first doomed marriage, to Adam’s mother (Lawrence lays on the hearts and flowers expertly, without resorting to schmaltz). Seeing the normally strong, unflinching Ben character in such a vulnerable position, is particularly enlightening (and very well played by Greene).

RELATED | More 1960s TV reviews

What doesn’t change this second season are the remarkably tight, thematically solid scripts that mark Bonanza as one of the best dramas on television at this point. It sounds simplistic, but the stories always have a beginning, middle and end (this is true “storytelling” in the best sense of the word: both basic and highly sophisticated in execution), while characters always have a subtext to their actions, and believable, layered motivations. While the obligatory “happy ending” will probably cause the most concern with modern viewers raised on nothing being settled in their television dramas (modern existential relativism is the easiest, laziest dramatic cop-out), it needn’t be. When seen in the context of what networks required back then in terms of keeping viewers “contented,” and more importantly, when seen in light of Bonanza‘s creator and producer David Dortort’s stated outlook for the show―positive and eternally optimistic―those happy endings work (“happy ending” is also a relative term; in The Courtship, Hoss is saved from a fallen woman with designs on his money…but he’s not happy about learning the truth).

Taken as a whole, there isn’t one bad episode this sophomore season. Standouts (minus the ones mentioned above) include The Mission, a straight-ahead desert adventure featuring the always-good Henry Hull as a decrepit, drunk scout looking for personal redemption out on the sand dunes. One of my favorites, Dan Duryea (he gets better and better every time I see him), has a terrific showcase for his completely unique blend of intelligent anti-hero charm and perversity, as the marvelously-monikered “Dude Butcher Boy” in Badge Without Honor (“Violence as such is vulgar…yet the skills and rhythms of disciplined violence, is beautiful,” he purrs―can you imagine that hack Tarantino ever coming up with something like that?).

Claude Akins, another familiar face I never get tired of seeing, plays against type in The Mill, belaying his often forceful, base physicality for a mentally-deranged character capable of manipulation and deception. The Trail Gang sports a typically quirky turn from Dick Davalos, who’s fine as a father-hating gunslinger. The Spitfire features a memorably flinty performance by Katharine Warren as proud settler who vows vengeance on the Cartwrights after she feels they’ve slighted and insulted her…as well as killing two of her boys.

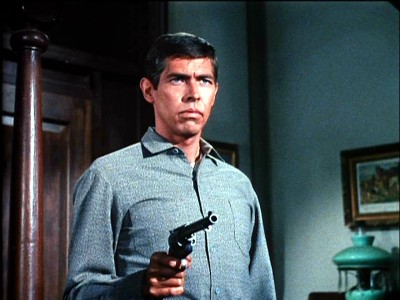

The Tax Collector is a funny entry from scripter Arnold Belgard that finds the Cartwrights’ ever-helpful attitude coming home to roost when they elevate the town layabout (Eddie Firestone) into a too-eager tax assessor. The Rescue includes the potent image of Ben getting (unfairly) whupped in a fight with Leif Erickson (can someone tell me if Erickson really was that loathsome in real life? Because he played that shtick better than anyone back then….). Dark Gate, written by Ward Hawkins and solidly directed by Robert Gordon, is a tense, unnerving suspenser featuring a socko performance by a young James Coburn as a friend of Adam’s who’s unknowingly turning into a psychotic killer (Coburn gets a showy, chilling fade-out as he chokes, “I’m sliding away, Adam. Where am I going?”).

The Gift features another remarkable lead performance from Martin Landau as Emiliano, a Mexican tracker who helps Little Joe deliver a beautiful white stallion for Ben’s birthday. Landau, one of the best character actors working in television at that time, brings subtleties to his character that aren’t readily apparent in the script, while boosting the level of performances from his surrounding players (Landon in particular benefits acting against Landau, while Greene has a memorably tender scene cradling and kissing his saved son, Landon). The Dream Riders, written by Jack McClain and James Van Wagoner, and directed by who else, Robert Altman, is a deceptively light entry that grows in sad meaning as Sidney Blackmer’s (excellent, as always) megalomaniac balloonist is shown ultimately to be a tragic, misguided dreamer (some very funny bits with Landon in a balloon basket, too).

Director Robert Altman returns again for one of the season’s best, the remarkable Silent Thunder, written by John Furia, Jr. and featuring one of Stella Stevens‘ finest performances (from one of the best―and most under-utilized―actresses of the 1960s and 1970s). Portraying a deaf mute, Stevens’ turn is simple yet highly effective, playing well off Landon’s sensitive Little Joe, while Altman gives us a brief yet dazzlingly expressive bit of direction when he shoots Steven’s almost-rape from her POV, complete with silent soundtrack and odd, ominous framing on her attacker, Albert Salmi (you never see direction like that in most formulaic television back then).

The episode, Sam Hill, that doubled as an unsuccessful spin-off pilot, features who else, director Robert Altman, at his weird, otherworldly best, creating a memorably mythic, ominous visual schematic that suits this tall tale to a T. You won’t soon forget the image of Hoss wildly hammering away at an anvil as a storm rages around him, or star Claude Akins, prettied up with eye makeup to look like a leading man, standing on a hill as lightning and smoke swirl behind him (one really has to give a lot of credit to Altman for helping to set the bar so high for Bonanza‘s early seasons).

Altman, however, didn’t direct my favorite episode this season―The Infernal Machine―written by Ward Hawkins. Veteran helmer William Witney (another unaware, unasked contributor to Tarantino’s dubious skill set) helmed this remarkable outing, a brilliantly realized episode that achieves remarkable switches in tone―from broad slapstick to delicate pathos to an almost perverse black humor―from the inspired cast. Witney’s big wrap-up, an homage to silent movie slapstick when Hoss fights the dastardly villains, is an astonishing flash of self-reflexive choreography that stands out even more against the playful, mocking tone of the piece―a wholly integrated work on a level you don’t often see, even during those days of everyday remarkable television.

The popular misconception (perpetuated by always-suspicious sites like Wikipedia) is that Bonanza was almost canceled until it was moved to Sunday nights (for its third season), away from Saturday night ratings giant, Perry Mason. That’s half true; Bonanza was almost cancelled after its first season against Raymond Burr‘s classic, but by this sophomore session, Bonanza, given a second chance by NBC due to their considerable investment in this first-color Western, was not only holding its own against Perry Mason on Saturday nights, but beating it on a regular basis by the end of the 1960-1961 season.

Bonanza, which didn’t even chart on the Nielsen Top Thirty during its first season, shot up to a healthy 17th for the year this sophomore session…only one notch below Perry Mason, which dropped from the previous year’s 10th position, to 16th this season. And just as confirmation of Bonanza‘s might against the long-time legal series winner, once Bonanza moved away from the legal drama to its traditional Sunday night spot for its third season, Perry Mason shot back up in the Nielsen’s to fifth for the 1961-1962 season, a spectacular comeback…but not as spectacular as Bonanza‘s 2nd place finish that same year.

A note on the copious extras for Bonanza: The Official Complete Series boxed set: if only Andy Klyde was in charge of more vintage TV DVD releases. First off, the original NBC bumpers, logos, and RCA promos appear on quite a few episodes. Photo galleries featuring original behind-the-scenes production stills are available for most, as well.

Commentary tracks are available, too. Scripter Anthony Lawrence talks about The Rival and Elizabeth, My Love (well-spoken and informative); Naura “Big Red” Hayden discusses The Infernal Machine (she’s funny as hell, too―great commentary), and Andrew J. Klyde give a terrific commentary on Sam Hill (a wealth of info here). Western star Ben Cooper provides a track for his Showdown episode. It’s quite informative, but he crushed me when he said, “See all that beautiful scenery? It’s all housing developments now,” (speaking for all TV fantasists who refuse to acknowledge the march of time, they should have edited that comment out).

Recently passed Stella Stevens herself has the single greatest intro I’ve heard from a star on one of these commentary tracks. Opening the discussion of her superlative episode, Silent Thunder, she seductively breathes, “Helloooo, it’s Stella Stevens,” in a manner that speaks volumes about this sexy, confident actress. Unfortunately…a moderator was sorely needed to get this commentary track back on track, with big patches of silence interrupted by brief notations from Stevens on what her character was thinking. I don’t need to hear Stella Stevens tell me what the character was thinking…her amazing performance already tells me. She doesn’t even talk about what it was like working with Altman. Just think what entertaining info and stories we could have had from the fascinating Stevens, had there just been someone there (…someone very much like me), asking her the right questions.

David Macklin has a funny sense of humor (and a funny take on TV history) in his entertaining commentary for The Blood Line, while lovely Julie Adams has some fascinating insights into the series’ production for her commentary track for The Courtship (her little self-deprecating laughs at the on-screen action are charming, and I’m curious to know more about her special friendship with one of my favorite character actors, Neville Brand).

Other extras include a brief, three minute video introduction shot in 1999, from Bonanza creator/producer David Dortort for the 40th anniversary of the show (it’s lovely to see his charming wife humorously correct him from time to time). There’s a fascinating series of stills from Lorne Greene’s and Michael Landon’s promotional visit to Cincinnati “Colortown, USA” Ohio, and their appearance on the real “Oprah Winfrey Show”: The Ruth Lyons 50-50 Club (a few parade stills from other events are included, too).

As well, there’s more video footage of David Dortort at his home, discussing the part historical accuracy and the importance of color played in the production of Bonanza, along with his thoughts on Pernell Roberts. There’s also a vintage on-air promo for the series, some on-set publicity photos of the cast, and a few stills of the lead actors at their homes, along with a very brief Dan Blocker interview with Richard “Cactus” Pryor (mid-to-late 60s), which only runs 1:39 (I would have liked to see the whole interview). An amazing amount of extras for a must-have vintage TV boxed set. Stay tuned for Season Three’s review!

Read more of Paul’s TV reviews here. Read Paul’s film reviews at our sister website, Movies & Drinks.

Another great, insightful review, Paul! Thanks for posting!. Can’t wait for your Season 3 review!

Hey, any truth to the rumor that you will be participating in the online 65th Anniversary salute to BONANZA this weekend? Sure would be great to see and hear you (as well as read your insights)!

AJK

LikeLike