“I’ve done things that would turn your blood to spit.” Cathy Ames

I know, I know. Months ago, I promised to review all of the miniseries that were featured on NBC’s “miniseries series,” Best Sellers. And I did. I even bought a bootleg DVD of the one that’s impossible to find—that’s how committed I was to the project. I only had The Rhinemann Exchange to go. Well…I’ve watched it. I have the notes. But I’m telling you: it’s so goddamn boring I’m not sure I can face writing a review of it. We’ll see. I don’t want to talk about it. Let’s look at a different mini. Come on—give me a break, okay?

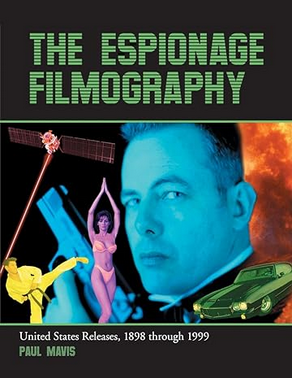

By Paul Mavis

Rescued from undeserved oblivion (I don’t remember it ever being re-run), Acorn Media released a three-disc, six-hour-plus boxed set of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden several years back (later re-released by CBS Home Entertainment), the 1981 ABC miniseries adaptation of Steinbeck’s massive novel. Far more faithful to Steinbeck’s original story than the more famous 1955 feature film directed by Elia Kazan and starring James Dean (which only covers the final third of the novel), John Steinbeck’s East of Eden has plenty of time to more fully explore Steinbeck’s generational plotline (adding a sense of depth and completeness to Steinbeck’s biblical allusions), while also allowing a full flowering of the Cathy Ames character, deliciously brought to evil-incarnate life by a wickedly beautiful Jane Seymour (it’s the single best performance of her underrated career). It would seem inevitable that viewers would want to compare this TV remake with the earlier, justly iconic big screen version—a comparison, within limits, that’s surprisingly favorable.

Click to order John Steinbeck’s East of Eden on DVD:

(Paid link. As an Amazon Associate, the website owner earns from qualifying purchases.)

A necessarily bare-bones plot summary of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden is best suited here not only because many people are only familiar with the plot from the abbreviated 1955 film, but the length of this miniseries adaptation precludes anything other than a brief rundown.

Connecticut, 1863. Union soldier Cyrus Task (Warren Oates), having lost a leg to a Rebel bullet, has returned from The War Between the States to his farm. His wife (Nellie Bellflower), a devoutly religious woman, is scornful of Cyrus’ phoney boasting about his brief war exploits, but is unable to deal with the knowledge that Cyrus has given her a sexually transmitted disease (“Cupid’s itch,” as the doctor calls it). Humiliated before God, she commits suicide by drowning herself in the farm’s pond.

Cyrus, at a loss how to raise his infant son, Adam, remarries and has another son, Charles. As grown young men, Adam (Timothy Bottoms) and Charles (Bruce Boxleitner) continue a destructive sibling rivalry, exacerbated by their competition for the love of their distant father. Charles, at times cruel and vindictive towards the weaker, kinder Adam, eventually stays with the farm while Adam is forced against his will to join the Army to fight Indians out West. Cyrus, meanwhile, has built his false war stories up into a thriving literary career, which segues into a government job in Washington, fighting for pension rights for Civil War veterans.

At the same time, beautiful, amoral, evil Cathy Ames (Jane Seymour) grows up in Massachusetts. Found exposing herself to two young boys in a barn, her pious mother (Grace Zabriskie) forces Cathy to say the boys forced her to do it, and then threatens legal action if the boys’ fathers don’t whip the naked boys in front of her and Cathy—an act that produces a pleased smile on the adolescent Cathy. Later in high school, after destroying the life of one of her teachers, Mr. Grew (Nicholas Pryor), who commits suicide on the church’s altar, Cathy refuses her father’s restrictions on her life (he demands she return to school) and summarily burns down her home—killing both her parents.

Brazenly seducing Jules Edwards (Howard Duff), a whoremaster who wants to keep Cathy for his own personal services, Cathy eventually turns on her benefactor, as well, who nearly kills her (after she cuts him with a knife) with a vicious beating. Slithering up to the porch of Charles’ and Adam’s farm (Adam has returned to the family homestead after wandering for some time after the Indian Wars), Cathy is taken in by the soon-battling brothers, with Adam eventually falling hopelessly in love with her (and foolishly idealizing her), while Charles sees right through her act (he says they’re the same devil).

After she seduces Charles (on the evening of her honeymoon to Adam—she drugs him to keep him out of the way), Cathy and Adam leave for California. On their idyllic ranch, Cathy becomes pregnant with twins—twins she utterly rejects, going so far as to shoot Adam a week after giving birth, a bid to escape his notion of a settled family life. With the help of neighbor Sam Hamilton (Lloyd Bridges) and his educated Chinese servant, Lee (Soon-Tek Oh), Adam recovers from his depression over Cathy’s departure, and moves the boys to Salinas, where rebellious Cal (Sam Bottoms) and pious Aron (Hart Bochner) mature, eerily fulfilling the same dynamic that existed between their father and their uncle.

The chief virtue of small-screen John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, aside from the compelling lead performance by Seymour, is the chance to see most of Steinbeck’s complex story enacted on the screen, something that wasn’t possible with the two-hour 1955 big-screen adaptation. There’s no question that from a strictly cinematic viewpoint, from an evaluation of the visual design and mise-en-scene, to the integration of the central performance by James Dean, that the 1955 movie is a superior “aesthetic whole,” if you will, in comparison to the miniseries.

Director Harvey Hart, limited perhaps by what was expected of the visual look of a TV miniseries at the time, keeps most scenes resolutely head-and-shoulders, relying on dialogue-heavy, short scenes (timed to fit between the commercials), to keep the plot moving. Hart, a veteran TV director, doesn’t have a sense of how to have the various themes of the piece flow from anything other than the actors’ lines, nor does scriptwriter Richard Shapiro (another long-time TV vet who would be best known for his involvement in the nighttime soap, Dynasty) transcend the expected limitations of a typical network dramatic offering from 1981—with the exposition kept relatively straightforward and unambiguous (although Shapiro does admirably maintain a period tone with dialogue that doesn’t sound anachronistic). While Hart’s structure may be more conventional than Kazan’s, this kind of basic storytelling can achieve a power through simplicity, particularly when the screenplay stays focused and drives on—which John Steinbeck’s East of Eden‘s does.

Hart and Shapiro do have plenty of room to introduce much more of Steinbeck’s work into the mini. Having recently watched the Kazan version, it struck me (when comparing the two) how at times, the motivations of the Kazan characters (through Paul Osborn’s script) can seem opaque and “rushed,” particularly after spending over six hours with Shapiro’s more faithful evocation of Steinbeck’s generational plot. The most successful element of that expansion is the full delineation of the Cathy character.

In the Kazan version, she’s a shadowy figure, referenced by other people more often than actually represented on the screen (and “removed” from our condemnation because of her advanced age and because we’re only told she runs a brothel…not that she was an enthusiastic prostitute, as in the novel). Critically, in Osborn’s script, Katy/Cathy tells Cal that she rejected Adam because of his goodness and his desire to hold on to her, to keep her away from other people, to “cage” her, if you will.

And with Raymond Massey’s portrayal of Adam emphasizing a religious rigidity (which this version avoids entirely), reinforced by Cal’s rejection of that morality, we have a far more sympathetic reading of the Katy/Cathy character in Kazan’s movie than Steinbeck may have intended. Although we’re told in the Kazan version that Cathy shot Adam, it’s an element of the two characters that doesn’t ring with much emotional depth, because we really don’t have a handle her character.

In John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, however, the full spectrum of Cathy’s awfulness is given free reign, and the portrait is overwhelmingly negative. We see Cathy right at the beginning of her life of evil, first as a child smiling with amusement and satisfaction when the two little boys to whom she exposed herself willingly, are whipped, naked, in front of her (after which she’s scrubbed clean by her mother—an act that Cathy will perform later in the series after she becomes an inveterate prostitute).

Later, she takes great delight in ruining her high school Latin teacher, before taunting her weakling father over his submerged understanding of what a true sociopath she’s always been. The mini makes it clear that she deliberately murdered her parents by burning down their house, and then shows her further manipulation of whoremaster Edwards, first by subtly suggesting he “keep” her, and then her final, corrosive humiliation of Edwards when she tells him how much he disgusts her with his touch (Seymour is particularly good in this tough scene, dancing in circles as she taunts Howard Duff with her delicious body and cruel, hard line readings).

Even after her beating by Edwards, she shows no sign of stopping her games, playing Adam and Charles against each other—just for fun—until she shows her true colors to Sam Hamilton during her birthing of the twins (another intense scene with Seymour, where she literally snarls like some kind of animal, shocking Sam, before viciously biting his hand and holding on like some kind of possessed demon). Adam’s understanding and love for Cathy (which isn’t shown as cruel or controlling or religiously motivated, as it’s suggested in the Kazan version) results not in her conversion over to goodness, but in an near-fatal shot from a revolver, pointed by an enraged, uncaring Cathy.

RELATED | More 1980s TV reviews

Her tenure in a Monterey brothel run by kindly Anne Baxter is equally perverse—she insists on still turning tricks, even when Baxter tells her it’s not necessary—before it turns homicidal. Finally, we see Cathy/Katy, reduced to a state near madness, as her evil nature totally consumes her soul (a creepy shot of Seymour, eyes rolling, her hands crippled by arthritis, is quite good). This is the Cathy/Katy of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden: an amoral, snake-like creature who turns on everyone with whom she comes into contact.

Another important character totally eliminated from the Kazan version is Lee, the Chinese servant, a character who illuminates one of the key themes of the novel but who is given quite a bit of screen time here. I’m sure there have been numerous papers and articles written uncovering all of Steinbeck’s religious allusions within East of Eden, but one that is front and center within the narrative is the notion of “timshel” (“thou mayest”), in Steinbeck’s conviction that man, in this narrative, is given a choice (through the Cain and Abel story in the Bible) between following good or pursuing evil.

Free choice comes from a divine source, putting man on a plane with god, which trumps any notions of being “born bad,” or being powerless to fight negative traits we may inherit from our parents. In the Kazan version, we do hear Adam tell Cal that man can choose to be good—a lesson Cal reiterates in the finale to the prostrate Adam, proving he had been listening to him all the time. However, in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, it’s a constant undercurrent woven throughout the narrative that achieves true weight—courtesy of the kind, wise Lee—after hours of listening to characters believing that they labored under the burden of carrying on hereditary traits of good and evil.

It’s a fascinating character (well played by Oh), and one that provides a further opportunity for the makers of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden to be more faithful to Steinbeck’s original vision (tellingly, in this more complete version of the story, Cal borrows the $5,000 he needs to plant a field of beans from Lee, not from his mother, Katy, as is depicted in the Kazan version—another Osborn invention that further softens the Katy character).

Where John Steinbeck’s East of Eden falters badly, though, in comparison to Kazan’s version, is in some of the key, critical performances. Seymour, as I wrote before, is a marvel here; anyone familiar with her in movies like Live and Let Die or Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger or even Dr. Quinn – Medicine Woman will be shocked to see her pull all the stops out in this sultry, sometimes scary performance. There’s an iciness to Seymour here, a flat, cold, hard quality she attains with a spooky stare that, coupled with her startling beauty, makes for a most arresting femme fatale performance.

Other cast members are memorable, as well, including Warren Oates, Lloyd Bridges, and Howard Duff (all of them total pros, as we would expect), along with nice supporting turns by Richard Masur and M. Emmet Walsh. However, the critical male leads for the Trask brothers and their sons can’t compete against Seymour’s strong showing here, giving John Steinbeck’s East of Eden a lopsidedness that’s readily apparent when Seymour’s character occupies less screen time during the final third of the film.

Timothy Bottoms, a good actor, has difficulty with the younger Adam Trask, and carries little weight as the older Adam (particularly when he’s supposed to be the father of Sam Bottoms, only four years Timothy’s junior). Nice guy Boxleitner, who’s physically right for Charles, the “bad” son who may be Cal and Aron’s father, simply can’t convey the danger and sexual threat that Charles should have; his character needs to be strong enough to linger on in our minds after he disappears from the narrative at the end of the first third of the mini, but we quickly forget about him (which we shouldn’t, considering how he may figure into the parentage of Aron and Cal).

Hart Bochner disappears on the screen as an ineffectual Aron, while Sam Bottoms has one of the most impossible tasks one could imagine for a young actor: step into a role made iconic by a young James Dean. Forgetting any comparison between the two actors, Sam Bottoms’ approximations of teenaged angst and his torn loyalties between the love and hate for his father and unknown mother, are just that: approximations. He simply doesn’t have enough of a distinctive personality for us to care about Cal as we should, let alone the technical chops that might have saved the performance.

These compromised, ineffectual performances in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden undermine the gained benefits of putting more of Steinbeck up on the screen; it’s too bad that more care wasn’t taken to either extract better performances from the actors cast here, or that better male lead actors weren’t recruited for the roles. Still…there’s the erotically corrosive tour de force turn by Jane Seymour as Cathy Ames, which is more than enough recommendation for this little-seen mini.

Read more of Paul’s TV reviews here. Read Paul’s film reviews at our sister website, Movies & Drinks.