Hey. We’re not stupid, you know. We watch serious things, too, here at Drunk TV. It’s not all cowboys and cavemen and jiggle TV. We got education. So apparently big time director Christopher “I’m Beyond Criticism Because My Movies are Long and Look Important” Nolan is ready to release a long, important-looking movie about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father” of the atomic bomb. Now, the staff here at Drunk TV never pass up an opportunity to ride a gravy train, so we thought we’d undercut ‘ol Nolan boy and release a review of a rival project. Not one for that laughable 1989 Roland Joffe Oppenheimer “epic” that starred Paul Newman’s trim little mustache, that creepy Noh mask guy, and Howling Mad Murdock. No, the old PBS miniseries, from 1980.

By Paul Mavis

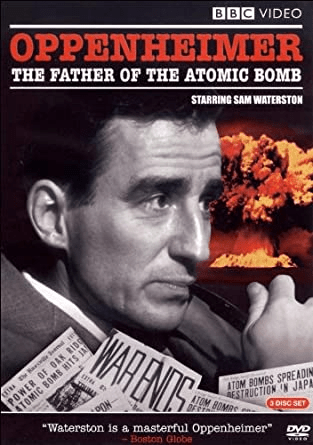

A few years back, BBC Video and Warner Bros. released on disc the six-part miniseries, Oppenheimer, a 1980 co-production between the BBC and WGBH Boston that first premiered here in the United States on PBS’s American Playhouse, in the spring and summer of 1982. Starring Sam Waterston as Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb,” Oppenheimer plays it relatively even-steven (…as much as liberal moviemakers making a mini for liberal audiences on liberal PBS could). Oppenheimer’s enthusiastic achievements in marshaling the massive “Manhattan Project” that delivered the atomic bomb to America (and a victory over Japan in WWII) are contrasted with exploring the foibles in his personal relationships, as well as his ill-considered naivete concerning global politics. Anyone looking to confirm their romantic, one-sided image of Oppenheimer as some kind of martyr to Cold War “witchhunts” of the 1950s, might want to look elsewhere (read M. Stanton Evans’ Blacklisted by History to get a whole new perspective on those so-called “witchhunts”).

Click to order Oppenheimer on DVD:

(Paid link. As an Amazon Associate, the website owner earns from qualifying purchases.)

Densely plotted, nothing but a short, condensed summary of events in Oppenheimer would be appropriate for this review. Beginning in the autumn of 1938, the miniseries begins in Berkeley, California, where pampered, tenure-safe professors, safe on the shores of peaceful America, dabble in radical politics as the world heads inevitably towards war (nothing changes…). J. Robert Oppenheimer (Sam Waterston, excellent as always), a professor of physics at the University of California, has, along with practical physicist Ernest Lawrence (Bob Sherman), built up the university’s physics department to rival the great scientific institutions in Europe.

“Oppy,” as he’s known by his students, is embroiled in a corrosive, destructive relationship with Jean Tatlock (Kate Harper), a depressive, disparaging socialite who belongs to the Communist Party. Forever goading Oppy to officially join the Party (his constant donations of money and time aren’t considered enough for the shrewish Tatlock), Tatlock has nothing but contempt for Oppy’s continued standoffishness in joining the cause―a move he feels will seriously hamper his career. He’s a committed “fellow traveler,” but he can’t take the final step to an official Party member…just like he can’t officially commit to Jean.

Two events―one personal, one scientific―combine to change Oppy’s life forever and catapult him from a moderately successful theoretician to a world famous figure. First, the knowledge that successful fission experiments in Europe will lead to a race for “super weapons” spurs Oppy to pursue a role in the government’s efforts to develop an atomic bomb. Pushing Oppy forward in this goal is his new wife Kitty Harrison (Jana Sheldon), a vivacious romantic partner who, quite unlike Jean, sees in Oppy an opportunist who can get ahead in his career during the coming war years.

RELATED | More 1980s TV reviews

Selected by gruff, no-nonsense Army General Leslie Groves (Manning Redwood, in a deceptively sly performance) to head up the government’s efforts to build an atomic bomb, Groves recognizes that Oppy’s scientific credentials, matched with his (conflicted) desire to make a real name for himself in the scientific community, is the perfect combination he’s looking for in a supervisor who can gather together the tens of thousands of vague scientific inquires, questions, and theories from the thousands of American scientists working on the bomb, and fashion a workable project that delivers the goods within the ridiculously short time they’re given.

Oppy, cognizant of the realities that are involved with the military running this massive scientific show (a reality the “head in the clouds” scientists detest), proves to be the perfect conduit between the scientists who constantly want to find the most “elegant” method of designing the bomb, and the military that wants something, anything that will blow up―and quickly, before the Germans and the Japanese beat them to the punch. Oppy succeeds beyond his wildest dreams, enthusiastically delivering up the bomb while at the same time, wringing his hands over the effects of its monumentally destructive delivery. However, once the war is over, and Oppy returns to his high-wire act of dangerously flirting with radical politics, the government, looking for political threats during the height of the Cold War, moves in to shut down Oppenheimer as a national “security risk.”

Seeing Oppenheimer again after all these years (I saw it when it first aired), I was struck at how careful it was throughout its six hour running time to portray Oppenheimer in a “fair” light. Except for a few significant omissions, Oppenheimer is unstinting in presenting a view of Oppenheimer that isn’t at all “mythic” or grandly, tragically heroic. This of course is tantamount to sacrilege for liberal historians and politicians who love to invoke Oppenheimer’s “martyred” name when discussing the issue of McCarthyism and the power of the U.S. military industrial complex in the 1950s. While politics certainly play a part in the mini’s larger outer view, Oppenheimer‘s script (from Peter Prince) always underpins the monumental political and scientific events in Oppenheimer’s life with his intimate, personal strengths and weaknesses.

Oppenheimer begins with the heady world of late 30s American university and college academia flirting with radical politics, asserting in the opening narration that many of these teachers felt socialism (and by extension, communism) was the only political theory that was dealing with the worldwide rise of fascism and militarism. Of course, these teachers believed this while willfully blinding themselves to the horrific, all-too-real effects of socialism and communism in Russia―a fact that Oppenheimer fairly points out when Oppenheimer mentions the disparaging comments from scientists who recently came back from working in Russia, scientists who were thoroughly disillusioned with the naive utopianism they previously held for the Communist state.

But no matter how aware Oppenheimer was of this seeming dichotomy between idealistic political beliefs and the harsh reality of the true nature of socialism and communism, he continued throughout his career to flirt with radical politics―a fact that the mini isn’t afraid to pin on Oppenheimer as one of the main sources of his personal and professional troubles. Why Oppenheimer did this is a trickier matter, but the script seems to suggest it was a combination of Oppenheimer’s reluctance to commit to anything, including going along with the military’s insistence that he function as a stereotypical loyal, patriotic American―something he most certainly was, but at the expense of his personal radical politics―and, as Groves states quite accurately, Oppenheimer’s refusal to face his own ambition.

The highly competent Groves (who is unfairly portrayed as a slightly buffoonish character here, as are all the military figures) states that Oppenheimer wasn’t any different than anyone else in their desire to “get ahead” and do great things. However, as an intellectual, Oppenheimer had to have the resulting consequences of that ambition―the death of tens of thousands of people at the hands of the A-bomb―”sugar coated” for him.

Oppenheimer is quite complex in showing an Oppenheimer who wanted to be both a radical and a thoroughly rigid “establishment figure” (it’s Oppenheimer’s initial idea to put the scientists at Los Alamos in uniforms with rank, not the military’s). Dichotomy of self-interest seemed to war constantly within Oppenheimer, according to the mini. Knowing that seeing Jean Tatlock was toxic to his own self-image, self-esteem, and self-worth, he still continues to see her―even though it jeopardizes his security clearance with Groves, and puts a strain on his marriage to Kitty.

Even though he expresses a desire to share atomic science secrets with the Soviets, he refuses to go along with such a plan when a friend, Haakon Chevalier (Peter Marinker), offers up this treason at war time. And when, quite sensibly, the military wants further information when Oppenheimer himself goes to military intelligence to inform on Chevalier’s espionage activities, he refuses to name anyone else Chevalier may have contacted. He even goes so far as to make up a story and lie about these activities to the military, when such an act, as he well knew from his own dealings with the military in Los Alamos, was a suspicious action that could be taken as a sign that he was sympathetic to these very same espionage activities.

And even as events heat up back in America immediately after WWII and during the start of the Cold War, Oppenheimer jeopardizes his own position in the Atomic Energy Commission when he continues to consort with Communists, including Chevalier, an admitted espionage agent, when such an act could only be described as a perverse desire on Oppenheimer’s part to see how far he could push the government and military before they lowered the boom on him. It’s unsaid in the script, but perhaps a strong masochistic―or even self-destructive―streak ran through Oppenheimer, as well.

As well, Oppenheimer is layered in its treatment of Oppenheimer as a conflicted pragmatist who recognized the great opportunity the “Manhattan Project” afforded him, while chronicling his equally conflicted views on the aftermath of the A-bomb effects. While most contemporary accounts of Oppenheimer’s activities like to stress the “blood on my hands” aspects of his guilt over the development of the A-bomb (a view that fits in perfectly with a majority of today’s writers who have their own political agenda; i.e.: we hate murderous America when it wins), Oppenheimer is much more balanced in showing how Oppenheimer actively sought out and embraced the development of the bomb for the express purpose of defeating Japan, going so far as to veto objections by other scientists like Lawrence who wanted to give Japan warning of what was to come.

Indeed, the tortured socialist Oppenheimer of Oppenheimer is at the same time a hardened realist who, in addition to believing that scientists aren’t the only ones to pass moral judgments on the results of their experiments (try that one today on bought-and-paid-for global cooling global warming climate change “scientists”), appreciated the opportunity the military gave him to develop a project he would never have realized in his university career. He also firmly believed in the “rightness” of developing the A-bomb in the first place―a fact that doesn’t go away despite Oppenheimer’s eventual back and forth equivocation, later in his career, over the development of the “Super,” the thermonuclear H-bomb.

Oppenheimer still can’t resist leaving out some of the more unsavory (to liberals, at least) aspects of Oppenheimer’s career―specifically the fact that the “martyr” of McCarthyism willingly and enthusiastically “named names” of “fellow travelers” during his final security clearance hearing, even though that clearance was due to expire anyway (if you’re shaking your head about those Cold War times, just remember that up until a few months ago, we had political leaders and tens of millions of regular Americans pushing for denial of medical care, denial of gainful employment, social ostracism, and even death for their fellow Americans who merely questioned their own government’s Stalinistic employment of lockdown, vaccine and mask mandates). That mercenary fact always seems to be conveniently left out when contemporary accounts of Oppenheimer revel in the thoroughly bipartisan government “witchhunts” of that time. Still, for much of the fascinatingly contradictory Oppenheimer, the portrayal of Oppenheimer is inclusive…and decidedly mixed. Something tells me that’s not going to be the case with the new big-screen Oppy….

Read more of Paul’s TV reviews here. Read Paul’s film reviews at our sister website, Movies & Drinks.

A brilliant and painstaking review, but my simplistic gut response, these assholes are just like the leftist elite we have now. I despise them. Collective elitist guilt stinks even more than their comrades in arms, the mighty media.

LikeLike

Amen, Barry

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would have said just like the right-wing extremists, taking away human rights for their own gain.

LikeLike

Put your real name on comments here. Why hide behind “anonymous”?

LikeLike

You appear to be an ideal contestant for the Raymond Burr Bowel Movement Contest, judged in the preliminary rounds by size, texture, color, and aroma. For the finals, flavor has been added.

LikeLike

Another great piece, Paul! I share your concerbut ns about the upcoming movie (although I’ll probably see it because there’s so little adult moviemaking anymore), but I’ll need to check this out as well. For yet another view of Oppenheimer, I’d recommend the unlikely (but oddly compelling) opera “Doctor Atomic.” Couldn’t imagine that as the topic for an opera, but it worked.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Mitch(ell)–to be honest, I don’t know which form you prefer! I think you’ll enjoy it. I’ll I check out the opera!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good question – I think I prefer the longer form we get with a miniseries–character development, etc. (See “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy” for example), but sometimes a movie can capture the atmosphere of a story in a way that can’t be duplicated on TV (“Quiz Show.”) I’ll just have to see them both!

LikeLiked by 1 person