Not-bad-at-all mid-80s indie miniseries, based on the international bestseller.

By Paul Mavis

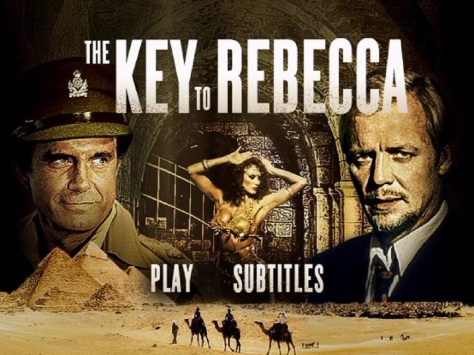

CBS DVD and Paramount have released The Key to Rebecca, the 1985 miniseries from Taft Entertainment, Operation Prime Time Productions, David Lawrence Productions, and Castle Combe Productions (originally syndicated here in the U.S. by Worldvision). Based on Ken Follett’s best-selling WWII espionage thriller, and starring Cliff Robertson, David Soul, Season Hubley, Anthony Quayle, Robert Culp (as, um…Field Marshal Erwin Rommel), David Hemmings, and (gulp) Lina Raymond, The Key to Rebecca offers a decent amount of suspense (and even some surprisingly kinky sex) amid the solid performances. Fans of spy flicks and ‘80s miniseries will like this one.

Click to purchase The Key to Rebecca at Amazon.

The North African desert, 1941. German military intelligence officer Alex Wolff (David Soul) collapses in the fiery desert, still clutching his two suitcases. Fortunately, he does so near the camp of his bedouin cousin, Ishmael (Terry Raven). Revived, Wolff tells Ishmael to guard one of his suitcases with his life, before he sets off again towards Egypt and Cairo. Given a lift into Asyut by a suspicious British officer, Captain Newman (Richard Gibson), who doubts Wolff’s claim he abandoned a car out in the desert, Wolff kills the aide assigned to watch him, when the aide discovers Wolff’s suitcase is stuffed with cash.

Captain Newman reports this crime to Cairo British intelligence officer Major William Vandam (Cliff Robertson), an American who joined the British forces when his wife was killed in a Luftwaffe bombing raid. Vandam’s mystery thriller-loving young son, Billy (Charlie Condou), lives with him, watched over by faithful servant, Gaafar (Marne Maitland). Vandam’s buffoonish superior, Colonel Bogge (Ellis Dale), cares more about cricket than a soldier’s murder, but crafty Vandam smells something: why would a man walk through 400 miles of desert to come to Cairo?

Now in Cairo, dressed as an Arab (Wolff’s father was Arab; his mother European), Wolff contacts insanely hot belly dancer Sonja El Aram (Lina Raymond), an old flame. His request is simple: conduct an affair with a British officer so he can access the British plans for defending Tobruk and Northern Africa. She agrees…as long as Wolff finds her another woman to join them in bed.

Meanwhile, Major Vandam is also recruiting for the cause. Former prostitute Elene Fontana (Season Hubley) wants to get to Palestine…but she has no means of support when her latest “benefactor” is busted for black-market dealing. Vandam offers her money and ticket out of Cairo in exchange for any information on Wolff. What follows is a cat-and-mouse game as Vandam desperately tries to find the elusive Wolff, who continues to steal information from Sonja’s lover, Major Smith (David Hemmings), handing Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (Robert Culp) victory after victory, with the ultimate prize being Nazi control of North Africa.

I do remember watching The Key to Rebecca back in 1985, primarily because I had a huge thing for Season Hubley (I saw Vice Squad at this little art house theater like, 5 times). For someone who watched way too much TV his whole life, an independent miniseries like The Key to Rebecca was also “must-see” programming, precisely because it wasn’t a “Big Three” network offering.

RELATED | More 1980s TV reviews

Growing up in the pre-cable era, I was fortunate to have a giant Channel Master antenna that picked up independent stations like Channel 50 in Detroit, where I could catch the really “cool” programs that weren’t featured on my local Toledo stations (stuff like The Avengers reruns, Bill Kennedy at the Movies, Sir Graves Ghastly, and of course, The Ghoul).

I’m positive my experience wasn’t isolated. When an unfamiliar TV movie or miniseries obviously not originating from the networks popped up in a local TV listing, a savvy television watcher took particular note. In the mid-70s, when advertising rep Al Masini had the brilliant idea to link up un-affiliated independent TV stations (stations that weren’t owned by, or locked into “Big Three” contracts) and create a temporary “network” of sorts that featured independently-produced, first-run shows that could compete for network advertising dollars, the “Operation Prime Time” consortium was invented. The consortium’s first effort, 1977’s Testimony of Two Men, from the Taylor Caldwell novel, rocked the indie stations’ ratings books, and for the next ten years, a steady stream of miniseries, movie events, and TV series flowed out to viewers looking for something different on the tube (original programming for cable networks and stations would eventually make the OPT business model obsolete).

By The Key to Rebecca’s 1985 premiere date, though, its kind of big-scale indie miniseries production wasn’t nearly as unique or even noteworthy to TV viewers as it had been just a few years prior (I remember it just appearing in the local listings, with no promo push). VHS renting/recording was changing how we watched TV, and original cable programming was beginning to explode, so something like The Key to Rebecca could easily have gotten lost with viewers. I couldn’t find any solid info on how well The Key to Rebecca did in its markets, but as Follett himself stated, the miniseries’ relatively paltry budget of only $5 or $6 million doesn’t seem to indicate that anyone thought this was going to be a blockbuster (eight years before, with OPT’s most notorious production, The Bastard—yes, there actually was a time in America when such a title for a TV show sparked outrage, with local newspapers refusing to advertise the name—the budget was over $3 million).

Certainly the casting didn’t seem designed to get people talking. Already-peaked leading men Cliff Robertson (long-past A-level on the big screen, and in the midst of a mild character actor comeback, after the Begelman outrage) and David Soul (with two recent high-profile series failures under his belt: The Yellow Rose and the notorious NBC Casablanca reboot), along with a leading lady whose name meant absolutely nothing in terms of ratings’ draw, didn’t signal high expectations (OPT would release only two more minis after The Key to Rebecca, before ceasing operation).

Most certainly, the biggest draw for potential The Key to Rebecca viewers back in ’85, was Ken Follett’s name. His novel had sold millions of paperbacks since its publication in 1980, so it was smart of the movie’s producers to stick as closely as they could to the author’s original storyline. Based, very loosely, on the exploits of real-life German spy Johannes Eppler, The Key to Rebecca’s mix of history-based wartime espionage and romantic/sexual politics was a potent combination, and a natural for a miniseries adaptation (truth be told, “miniseries” is stretching it a bit, when there are only 2 parts to this, running a little over 3 hours total without commercials. “Long movie” is more like it).

Distractions do come from the relative cheapness of The Key to Rebecca (Rommel’s Panzer corps is one truck and one Volkswagen “Thing”), a poor, derivative musical score (composer J.A.C. Redford helps himself to some barely-altered cues from Patton and Vertigo), and the necessity (back then) for a largely head-and-shoulders visual schematic. And if things drag just a bit at times during the 194 minutes (all those repetitive scenes between Robertson and his kid, for starters), a bit of suspenseful subterfuge or some action or some teasing sexuality—along with several good performances—jolt The Key to Rebecca back onto the rails.

None of the characters or themes in The Key to Rebecca are terribly unique or original, but they are dealt with in an admirably tart, straight-forward manner. Wolff, the dashing, handsome anti-hero we’re supposed to root for, (even though we know we shouldn’t) remains an amoral killer without redemption, thankfully. As the movie progresses, he becomes less “romantic” (in the heroic sense) in our eyes, and thoroughly more loathsome…as he should.

Robertson’s Army major is just as ruthless in his mission (he repeatedly puts lover Elene in harm’s way, and even risks his son’s life, when Bill is taken hostage by Wolff, until he can gain a better advantage at stopping the spy), and just as manipulative in terms of sexual blackmail. Wolff appeals to Sonja’s grosser, base needs (her love of rich, expensive foods and wine, as well as constant sex), forcing her to make love again and again to the British officer so he can steal secrets, with Wolff’s abandonment (he left her once before, for 3 years) as punishment if she doesn’t.

Vandam is no different, coldly telling Elene to “do another man” if she has to, to survive in Cairo, before convincing her that if she wants rent money and a ticket to Palestine…she has to do “whatever it takes” to get Wolff to take her back to his place (so Vandam can find his radio and the code “key”). Follett (or perhaps more accurately, screenwriter Samuel Harris) gives us an “out” for Vandam, a reason to distinguish him from Wolff, by having him be first, genuinely sorry that Elene has to do this; then, telling her it isn’t necessary for her to go with Wolff one last time, when she begs off. He’s now in love with her, and doesn’t want to risk her life—something Wolff would never understand.

It’s actually Elene who insists on one last stab at nabbing Wolff, hoping to prove her love to Vandam, while also showing her loyalty to the cause in helping to defeat the approaching Germans. She’s even willing to play the game all the way down the line, stripping down and having sex with Wolff…and with Sonja, too, when she joins the couple in bed (a palpably erotic scene, with some then-titillating frontal nudity—a rarity, still, for 1985 non-cable TV). That’s an aspect of The Key to Rebecca that I wish had been explored more thoroughly: Elene’s barely-acknowledged attraction to the dangerous, seductive…but also charming and romantic Wolff, and her fear of seeing him again after their first “date.” That’s clearly how Hubley and Soul play their romantic scene together, shot on a moonlit bridge. However the script, unfortunately, doesn’t elaborate any further on this interesting twist for the Elene character.

Thanks to The Key to Rebecca’s extended format, there’s plenty of time for us to see these relatively complex characters intertwine. Fortunately, the conventions of the wartime espionage drama aren’t ignored, either. The mystery itself is surprisingly suspenseful; the tension of whether or not Wolff will be captured is sustained reasonably well throughout the movie, with director David Hemmings (yes, the actor, who also plays Major Smith) knowing how to stage an exciting sequence when called for. Amid the throat cuttings and broken bottles to the face, there’s a lovely-shot chase through dark, empty Arab streets, with menacing shadows and tight cuts and edits that’s a nice treat (director Hemmings saves his most showy tricks for, of course, his own on-camera death scene, via a knifing in a tub. We see his assailant up through the bloody water).

The cast, for the most part, is spot-on. 60-year-old Cliff Robertson may look a bit frazzled around the edges, but he has that old-timey, big-screen leading man weight and assurance that makes his Major Vandam character instantly authoritative. David Soul, looking jackal-lean and muscular, is particularly smooth and silky in his villainy, convincing us that he could equally and sincerely charm (or is it sincere?) hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold Elena, as much as he could enjoy sexually blackmailing perverse Sonja…or shoot Vandam’s son at the blink of an eye. Critics today will say old pro Anthony Quayle’s brief-but-jaunty portrait of an Arab thief is “racist,” but then everything, including “nude stockings,” is racist today, so who cares? He’s a pleasure, as always.

The Key to Rebecca almost becomes camp when hilariously self-important actor Robert Culp shows up as no less than Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, complete with a German accent that wouldn’t have got him past the Hogan’s Heroes’ casting door: “Perhapsz zats iz vhy zey loze battlez zan winz zem” (what in god’s name were the producers thinking here?). Camp does arrive, thank god, when painfully luscious Lina Raymond slithers on screen, her overripe body perfectly objectified by director Hemmings. She gives The Key to Rebecca a carnal, comedic jolt that’s much needed over the long haul (her scenes with Hemmings—“Don’t bite! Please don’t bite, Sonja!” are laugh-out-loud amusing). As for Season Hubley, she has the requisite good looks to be a believably desirable spy (she’s a wow, curled up nude on Robertson’s couch, with her shiny dark hair and piercing blue eyes). And you buy she’s a tough cookie who before has had to barter and trade her sex with men. What I always find interesting with Hubley is her tangible vulnerability. Whether its personal or professional, it unmistakably comes through the camera lens, lending her scenes a weight that isn’t warranted, frankly, in the script or direction. Her turn here is one of the best small surprises in the adroit spy meller, The Key to Rebecca.

PAUL MAVIS IS AN INTERNATIONALLY PUBLISHED MOVIE AND TELEVISION HISTORIAN, A MEMBER OF THE ONLINE FILM CRITICS SOCIETY, AND THE AUTHOR OF THE ESPIONAGE FILMOGRAPHY. Click to order.

One thought on “‘The Key to Rebecca’ (1985): Intrigue, suspense & threesomes power indie spy miniseries”