If you’re like me (poor you), you keep your remote handy to check out the local digital stations that air old-timey television, channels like MeTV, Cozi, and Antenna (don’t even mention Retro TV to me—they ditched my city right when the Althea and Nick Bellini fights were getting good on The Doctors). Twenty years ago, if you had told me I’d actively seek out television showing edited classics interspersed with commercials, I’d have said you were crazy.

By Paul Mavis

After all: that was the whole point of the evolution of cable, VHS and DVDs, and now streaming: unedited, uninterrupted classic content when you want it. Right? So…why regress? What’s missing? Ah…the nostalgia factor. That’s right—it turns out it’s kinda fun to watch television the way we used to, commercials and all. And this is even weirder: my younger kids, who only caught the very tail end of cord-tied TV, have fun watching commercial TV, too. Wanna know why? All the breaks allow them to screw around on their phones. One of the many benefits of their addled attention spans.

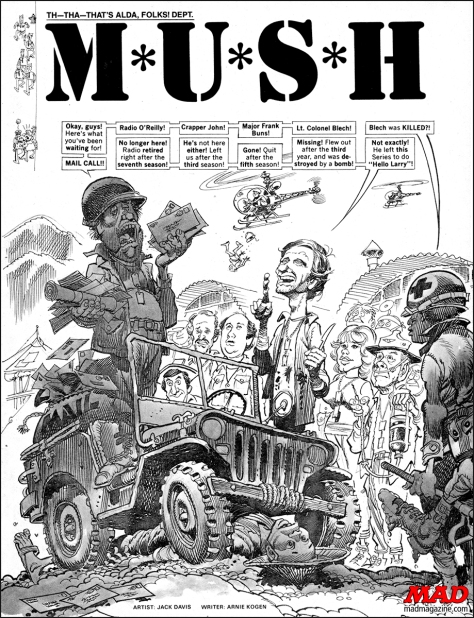

Click to order M*A*S*H: The Complete Collection at Amazon.

Your purchase helps pay the bills at this website!

So recently I tuned into MeTV because every other alert on my Facebook account was screaming that the 1983 series finale of M*A*S*H was going to air, and if I knew what was good for me, I’d better tune in or else. Now…I never watch M*A*S*H anymore, probably because any show will eventually stick in your craw if you watch it too many times, and hoo boy does that describe M*A*S*H for me. Just too, too much. However, I hadn’t seen the finale in years and years, and not being a fan of it at all, I thought I’d tune in and confirm how right I always am about these sort of things.

Couldn’t watch it. Not because the episode was awful (it was), but because MeTV is seriously speeding up the syndicated video transfers of M*A*S*H (to insert more commercials), giving the show that dreaded “soap opera effect” smoothing that makes it look like the actors are 4k Sims characters acting out scenes in your living room. For 30 seconds it was hilarious…and then I couldn’t take it anymore and switched off. Instead, I slid back the secret panel in my library and descended—via express elevator—1000 meters below the surface to my vast subterranean DVD vaults, where I eventually located (north wing, substation 7, “G” block, hallway 23, vault 13E) my old M*A*S*H: Martinis and Medicine Complete Collection DVD box set. No motion smoothing here…but also no feminine hygiene ads. Can’t win ‘em all.

I was seven when M*A*S*H premiered on CBS in 1972, and eighteen when it ended in 1983. I grew up with M*A*S*H being one of the most talked about and viewed TV shows during those 11 years (14 Emmys, 9 seasons in the Nielsen Top Ten…although interestingly, never number 1). As a little kid, I watched it on our black and white set with my old man (he quit when Wayne Rogers quit), and as an 18-year-old high school senior, I watched the Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen finale over at my girlfriend’s house (gee…what a fun party that was). Regardless of how I see the series now, M*A*S*H was a huge part of my TV viewing experience, at that most influential age span.

During the first four or five years that M*A*S*H originally aired, I never missed the show. After some significant cast changes, and a discernible shift in the series’ tone, I would view it more sporadically, checking in occasionally to see how it was doing. I wasn’t exactly a fan of the later seasons; M*A*S*H had become far too strident in its various social and political messages, while its comedy had become too rote and forced for my tastes (once you’ve seen Alan Alda do Groucho about, oh…a thousand times, it’s enough).

But still, when the final Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen episode aired, I felt some kind of “loss,” if you will, for a show I had grown up with finally ending. It didn’t particularly matter that M*A*S*H in later years didn’t appeal to me. Like a friend who’s been with you for years, the actual years together count just as much as any other aspect of the friendship (or in this case, the quality of the show itself).

RELATED | More 1970s TV reviews

When I was a kid, the original movie version of M*A*S*H was generally considered the raunchiest, funniest comedy released up to that point (man how times have changed). It was one of those movies that your parents would laugh about, on the q.t., when you started to listen a little too closely to what they were recounting. So I remember being quite excited about the TV series starting in 1972. Even at that age, I knew that nothing remotely objectionable would be broadcast on a network series, but maybe I would get a glimmer of what my parents had been quietly snickering about.

And I wasn’t disappointed (nor were they). Contributing many of the first four years’ wittiest scripts, veteran comedy writer Larry Gelbart (Your Show of Shows, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum) set the tone for the rest of the series, expertly mixing social criticism with some of the best one-liners this side of Woody Allen. The first three years’ worth of episodes of M*A*S*H are amazingly adept little satires, sometimes overtly silly (Five O’Clock Charlie), sometimes surprisingly deep (Sometimes You Hear the Bullet). Aided by a stable of other writers and directors working on the same wavelength, Gelbart and frequent director Gene Reynolds crafted, week after week, episodes that are still considered by fans to be the series’ best.

After a shaky first year in the ratings, where the show was almost canceled (it was getting killed on Sunday nights by The Wonderful World of Disney on NBC and The FBI on ABC), a move to CBS’s still-legendary “wrecking crew” 1973 Saturday night line-up (All in the Family, M*A*S*H, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Bob Newhart Show, and The Carol Burnett Show) catapulted M*A*S*H into the public’s consciousness, and firmly affixed the cast into people’s affections (the show went from 46th in the Nielsens, to 4th—thanks number 1 rated show, All in the Family).

Alan Alda’s hammy one-liners and Wayne Rogers’ roguish charm provided beat-perfect comedic timing. The team proved to be expert foils for the supremely gifted Larry Linville and his creation: the weaselly, paranoid, and very possibly insane Major Frank Burns (for my money, the series’ single funniest character). Gary Burghoff continued his Radar O’Reilly character over from the feature movie (a character who oddly switched from knowing to naive and back again, with regularity), while Loretta Swit proved to be simultaneously sexy and funny as the rigid, yet smoldering, Major Margaret Houlihan.

RELATED | More 1980s TV reviews

William Christopher was delightfully square and compassionate as Father Francis Mulcahey, and the addition of Toledo’s own Jamie Farr in 1973 added an element of the surreal to the proceedings with the cross-dressing, Section 8-seeking Corporal Max Klinger (either you like Klinger hang-gliding in The Trial of Henry Blake…or you don’t). And watching over all of this chaos was the commanding officer of the 4077th, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Blake (McLean Stevenson). Stevenson’s timeless Midwestern appeal, combined with an endearingly bumbling, sweet (yet still philandering and hard drinking) take on the character, really rooted the comedy during these three years. For a show that was decidedly anti-authority, despite Hawkeye’s and Trapper’s disregard for Henry’s leadership skills, Stevenson was still able to impart the necessary audience anchor for the show’s wild and woolly antics (an anchor that the producers obviously felt was still needed when Stevenson left, putting in solid, regular-Army character Colonel Potter in Blake’s place).

So it came as a great shock when the show’s producers killed off Henry Blake at the end of the third season. Here was a character that the American public had come to love (certainly of all the characters on the show over the years, his was the most accessible). And he was killed off, right when the public expected his departure from the 4077th to be a sad, but ultimately happy one. Just like that: dead. Of course, that’s the reality of war; M*A*S*H never again achieved the purity of that message than in that stinging moment when Radar comes into the operating room, and announces Henry’s death. It was a daring artistic move that paid off.

It was also perhaps the series’ only real true tragedy behind the cameras. Stevenson, whether on bad advice from his own handlers, or going by his own thinking (I’m betting on the latter, from what I’ve read), fatally crippled his career when he left M*A*S*H for a long term contract with NBC. He abandoned a celebrated part he could have conceivably played for the next eight years, to star in garbage like The McLean Stevenson Show, Celebrity Challenge of the Sexes and most notoriously, Hello, Larry (the cast and crew—rightly concerned that the loss of a major star could derail the popular series—begged him to stay…to no avail). Stevenson would later admit that leaving M*A*S*H was a catastrophic mistake.

Equally disconcerting was the premiere episode of the fourth season, where we learned that Trapper John had also left Korea. Talented Wayne Rogers, tiring of his increasingly second-banana role to Alda (the facts of his departure are still shadowy…some sources say a jealous Alda pushed for his departure), quit the show over the summer of 1975. Amazingly (for such a popular character), his character was unceremoniously dispatched, without even a final goodbye scene to the audience (a final slap to Rogers’ face that can only indicate malice on the part of…someone behind the scenes). Many fans and critics talk about the famous Henry Blake departure, which unfortunately seems to have overshadowed the shabby way Trapper was dismissed from the series.

Rogers, an extremely ingratiating performer, had a solid lock on the Trapper role. He took a character that could have been a shadow next to the central Hawkeye role (especially since the writers were skewing towards Alda’s Hawkeye), and making it his own with a combination of that ever-so-slight Alabama twang, and an alternating cocky/laid-back way with his delivery. Although Rogers didn’t have the career troubles that Stevenson had after leaving M*A*S*H (he had another successful series, House Calls, and numerous other TV roles…all while becoming a financial business whiz), his absence, along with Stevenson, was felt by loyal viewers who had come to see the cast of M*A*S*H as a family.

As for the new “Swamp” occupant, I personally couldn’t stand Roger’s replacement, Mike Farrell. As B.J. Hunnicut, the bland, painfully unfunny Farrell, in my mind, was specifically picked to stay firmly in Alda’s shadow (something Rogers obviously wasn’t willing to do). Farrell always seemed uneasy delivering the rapid-fire quips that Rogers would have tossed off with ease. Nor did it make sense in the beginning to have the devoutly married family man Hunnicut often referred to, along with Hawkeye, as some kind of rake with the nurses (Hanky Panky, Movie Night). I’m not surprised that I can’t think of a single “Mike Farrell” role either before or after M*A*S*H.

The inclusion of Harry Morgan as Colonel Sherman T. Potter was a somewhat more successful addition to the cast. Morgan, a veteran of decades of movie and television show appearances, struck a confident note as the by-the-book, regular Army commanding officer, who at the same time was understanding and tolerant of the shenanigans going on at the 4077th (too tolerant, actually, with the character eventually tearing up and sniffling at the slightest provocation). He proved popular with viewers…but I missed the lovable, incompetent, bumbling Henry Blake.

And while I enjoyed David Ogden Stiers as the stuffy, haughty, brilliant Major Charles Emerson Winchester…for about 3 episodes (that shtick grew old fast), he was no substitute for Larry Linville’s hilariously twisted Major Frank Burns (who could have been?). Following the departure of Stevenson and Rogers at the start of the fourth season, Linville had two more years of playing Burns (the only reason I tuned in); his marvelously psychotic portrayal helped keep the original tone of the show during those transition years. Remarkably, he wasn’t given a farewell episode, either, with his last, desperate acts in Tokyo to find his paramour Margaret, only relayed to the audience via a one-sided telephone conversation. It was another makeshift, disrespectful ending for a beloved character (sentimental the M*A*S*H producers and cast were not, apparently…).

With Linville’s departure, much of the original madcap spirit of the show left, as well. At that point, I tuned M*A*S*H out. Gelbart had left after the fourth season, with director Gene Reynolds gone after season five. Frequent contributor Burt Metcalfe became the de facto director of the series, with Alda taking a more central role in producing, writing and directing the series, as well (it may as well have been re-titled “The Alan Alda Show”). Comedy was becoming much more subordinate to the drama on M*A*S*H; the “message”—whether it was women’s liberation, the horrors of war, the various personal foibles of Hawkeye Pierce (and to a much lesser extent, the other characters)—became king.

The satirical nature of criticizing American military efforts—and later by extension, the American government and various aspects of American life and culture in general—became more pronounced, and less affectionate in the ribbing. M*A*S*H was quickly turning into a liberal political screed that was less and less an enjoyable entertainment, and more and more a weekly lesson and haranguing lecture that I didn’t need to hear over and over again. The repetition of the facile messages—war is bad; American culture is faulty; men are screwed up in comparison to women—quickly reached the saturation point, and made tuning into the series, frankly, a trial. M*A*S*H quickly moved into overkill, its best messages delivered years before the final fadeout.

The best example of this, ironically, was the summing up of M*A*S*H: the final episode, Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen, a hodgepodge of disparate storylines that illustrated all too clearly the show’s artistic dead end (there were way too many writers—eight, count ‘em, eight!—working on the script for any semblance of cohesion). How many times had we already seen Hawkeye pushed to his psychological limits? The catalyst for his actual breakdown, a breakdown that included almost botching an operation (which tellingly, Alda failed to show the audience), was a Korean mother smothering her infant to keep it quiet, when a North Korean patrol goes by a military bus. Unfortunately, it works more as a gimmick to illustrate Hawkeye‘s problems, rather than a stand-alone, horrific event for the Korean people (it’s also very similar to a plot development in the WWII film, The Counterfeit Traitor, where Klaus Kinski smothers himself to keep quiet as a German patrol searches for some escapees).

How many times had we seen Winchester bemoan the cultural desert that was the 4077th (his reaction to the Korean orchestra’s efforts is sickeningly saccharine)? How many times had we seen Father Mulcahy go above and beyond for the orphans down the road? And on and on. Clumsy script construction led to an awkwardly shot episode that had little flow from storyline to storyline, with the seams of the various individual scriptwriters’ vignettes all too visible (and those verkakte dream sequences…).

Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen may still hold some record for Nielsen ratings, but it’s a rather weak—and typical—later episode that indicated the series was long overdue for saying goodbye. Still, taken as a whole, M*A*S*H was a remarkable artistic achievement that helped push the boundaries of traditional TV fare, while entertaining millions of loyal fans all over the world throughout the 1970s and 80s…and for the next four decades in its umpteenth syndicated—and sped-up, smoothed-out—reruns.

PAUL MAVIS IS AN INTERNATIONALLY PUBLISHED MOVIE AND TELEVISION HISTORIAN, A MEMBER OF THE ONLINE FILM CRITICS SOCIETY, AND THE AUTHOR OF THE ESPIONAGE FILMOGRAPHY. Click to order.

Best piece ever on MASH. Mike Farrell was someone to keep away from, but Wayne Rogers, just fine, and I am delighted you made a clear distinction between the pair. On a semi-personal note, Don Weis and Rebecca Welles were closed and good personal friends. My wife, one Sunday afternoon in Santa Fe asked Don who the best actor he ever directed was, and he said: Alana Alda, (a beat), but Raymond Burr was the best reader.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Barry!!

LikeLike

Thanks for your insider insights, Barry. Here’s a footnote you may not know about. In an attempt to insert some feminine aspect to BONANZA, NBC publicists sent along two lovely ladies “for the locals to ogle at” (along with the unknown cast) at the World Premiere of the series in Reno in the late summer of 1959. Who did they send? Young and comely actresses Rebecca Welles and Selette Cole. Did Rebecca perchance share her recollections of that fateful weekend jaunt?

LikeLike

I think Harry Morgan did a fine job (a difficult task if there ever was one) of replacing McLean Stevenson. The key was that his Potter was more a “father figure” and Blake had been a “big brother figure”. I liked the fact that Potter didn’t put up with Burns’ and Houlihan’s bullsh*t like Blake (almost) always did. I also appreciated the “Pissed-Off Potter” episodes that seemed to occur at least once per season. I also could never imagine Blake “bitching out” Margaret’s father into manning up and treating her like a human being (like Potter does in one of my favorite moments).

LikeLiked by 2 people

“ I’m not surprised that I can’t think of a single “Mike Farrell” role either before or after M*A*S*H.”

I chuckled as I read your comment- the ONLY Mike Farrell role I can recall is when he played a crazed astronaut with super strength on the Six Million Dollar Man prior to MASH. I think that role worked as the tall, thin, bland Farrell really seemed crazy as he would be that last guy I could imagine howling, grunting and throwing boulders. His best work!

Also, I loved the rapid fire zingers and quips from the large ensemble cast in any of The Swamp scenes. For me it was a big loss when The Swamp was downsized and they removed Spearchucker Jones and Ugly John. Now there are 2 characters that could never appear in any reboot lol.

LikeLike

Another fine and thorough analysis by master reviewer Paul Mavis. But an important detail omitted: The picture and sound quality of the episodes in the official DVD collection released by Twentieth Century-Fox, and whether there are bonus bits included. Just wondering . . .

And I do want to put in a word for Mike Farrell. He did a fine job as a morphine-addicted doctor in an episode of BONANZA’s final season. Three years before joining the M*A*S*H unit, Mike’s character presciently tells Ben Cartwright (Lorne Greene) “I was a surgeon in an Army medical unit during the War.” (Of course he was talking about the Civil War.) He gave an impressive performance (although admittedly there was nothing funny about it).

LikeLike

Andy! Happy Holidays to you! Here are the bonuses (my editor isn’t all that concerned with that aspect of the reviews, unlike DVDTalk. He’s more…opinion oriented:

LikeLike