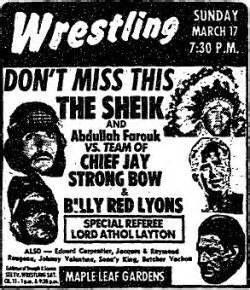

You know what sports I played as a kid? My TV, that’s what. And my favorite of all time was catching Big Time Wrestling coming out WXYZ, Detroit’s Channel 7. When Bobo Brazil, after breaking free of The Sheik’s camel-clutch hold, would give his skull-crushing “Coco Butt” to lay the Sheik out, well…why the hell would I want to go outside and toss around a ball and maybe miss that?

By Paul Mavis

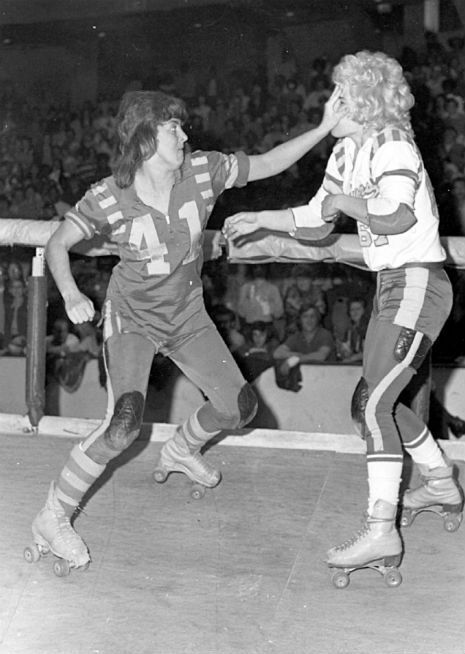

A few years back, VSC released The Roller Derby Chronicles, a highly entertaining three-disc set devoted to the history of this wholly American sport. Featuring Rolling Thunder, a fascinating documentary on the game’s evolution; 1971’s celebrated cinema verite documentary, Derby; and hours and hours of vintage game films and tapes from matches spanning the 1950s through the 1970s, the sum total of The Roller Derby Chronicles set is the most thorough examination of the sport I’ve encountered on disc (yaaaaasss it’s a sport). So tip the BarcaLounger® back, snag your wooden bowl of Beer Nuts®, crack open a cold brown bottle of Stroh’s®, and settle in for some high-powered skating and some head-bustin’ jamming!

Click to order The Roller Derby Chronicles:

ROLLING THUNDER

Produced in 2009 for Canadian television and directed by Larry Gitnick, Rolling Thunder looks back at the founding of the sport during the Great Depression, all the way up through its heyday and ultimate demise during the 1970s (“demise” is correct because what exists of “roller derby” today has little to do with Seltzer’s entity, either in conception or execution). According to Rolling Thunder, roller derby was invented by film promoter Leo Seltzer, who had had earlier success promoting dance marathons that were popular during the late 20s and early 30s.

Combining that format of entertainment masquerading as a sporting event, with a sudden roller skating craze in the mid-30s, Seltzer eventually built a touring “roller derby” competition made up of teams that were culled from local skating clubs he organized all over the country. At this point in the derby’s evolution, Seltzer emphasized the sporting aspects of roller derby over any staged shenanigans.

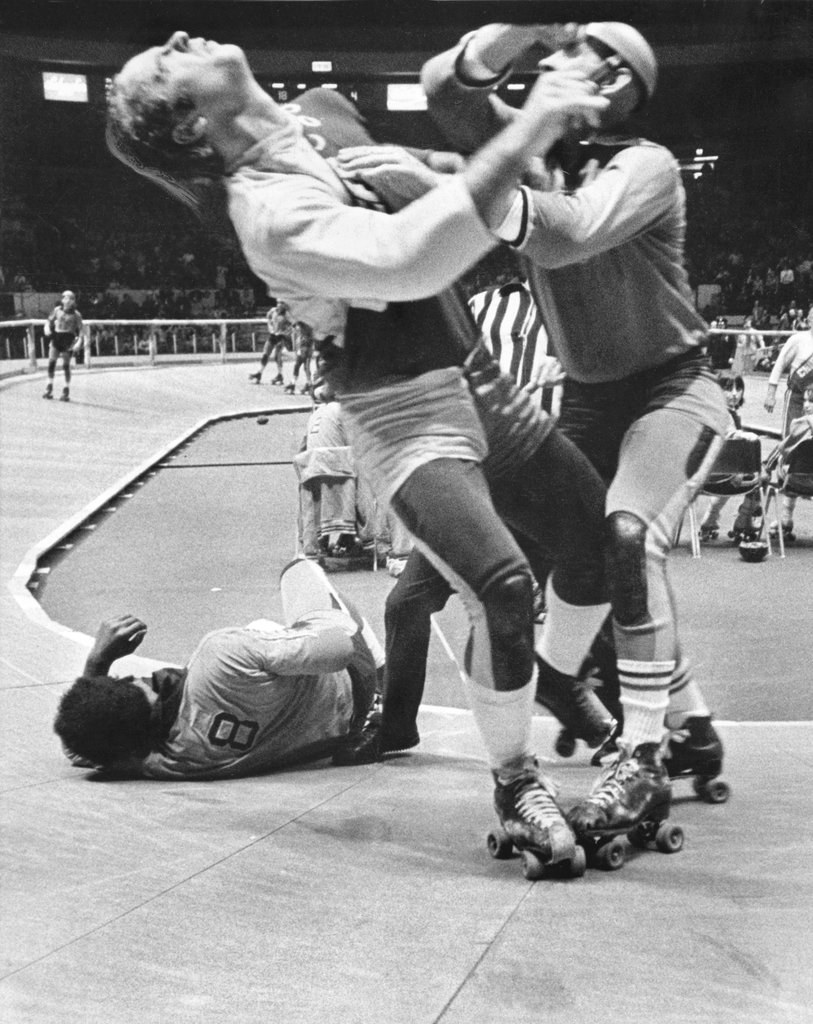

However, it soon became apparent that roller derby would go the way of other traveling marathon sporting events such as bicycling or dance competitions if it didn’t offer something new to the rowdy Depression-era spectators who wanted action. With an assist by celebrated author and roller-derby co-inventor Damon Runyon (can you believe it?), who pushed Seltzer into loading up derby competitions with contact moves (such as the always popular smashing into and over the track’s rail) and “fights” (not real, but still physically punishing), Seltzer soon had a massive, crowd-pleasing “sport” on his hands.

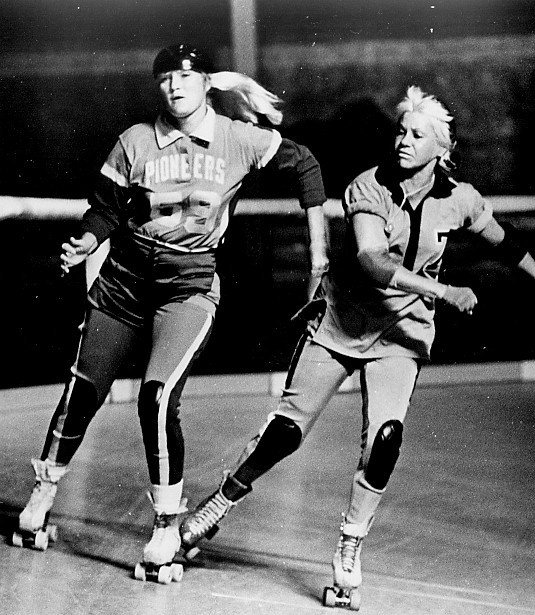

After much trial and error, Seltzer hit upon a successful game formula. Two teams of five skaters would race each other counterclockwise on a banked track, as appointed “jammers” tried to score points by lapping the other teammates. For each player lapped, the jammer’s team got a point. There were eight periods of play, with men and women skaters alternating on the track. Games weren’t “fixed” at this point, and Seltzer discouraged the skaters from playing up to the audiences with outsized theatricality.

Seltzer eventually franchised his derby out, with as many as six teams under his control touring the country. Although WWII dealt a body blow to the sport, it came back stronger than ever immediately after the war, due in no small part to Seltzer’s use of TV airings to build crowds. According to Rolling Thunder, the derby’s debut on television (the doc says it was the Dumont network, but other sources say CBS) caused a sensation with audiences, with both TV and in-arena audiences inflating each other into truly impressive numbers (over a five day period, some 80,000 people showed up for derby matches at Madison Square Gardens in 1951).

TV would eventually hurt the sport in the 50s when audiences began to dwindle. As more people owned their own set, they quit buying tickets to the live events, opting to stay at home and watch for free…which choked off the sport that made its money not from TV licensing fees (which were relatively paltry), but from gate admissions. This love-hate relationship with television would repeat itself again in the 60s and 70s when Seltzer’s derby enjoyed a surprising resurgence.

With son Jerry Seltzer at the helm of the organization in 1958, he eventually hit on an idea of syndicating game tapes of the few remaining derby matches that survived out on the West Coast, to local TV stations across the country. While syndication fees for the tapes were small, some advertising time was kicked back, as well, and with the successful re-introduction of roller derby to a new generation of TV fans, the national touring teams of the derby could continue again, reaching even bigger crowds at mainline venues.

Eventually, several factors conspired to end Seltzer’s derby, including the oil embargo of 1973 (it was no longer economically feasible to maintain the touring teams, with profit margins so slim and gas, when not rationed, skyrocketing in price), a decline in the quality of the skating as new, inexperienced skaters were added to the rosters, and overexposure on TV (a fad’s a fad, after all). Roller derby lives on today in local organizations, but it isn’t a solitary business entity like Seltzer’s derby, nor does it reach millions of TV and arena fans as it once did during its golden age.

Rolling Thunder, hosted by celebrated track announcer Donald Drewry (he intros all the discs here), gives a good generalized overview of the sport for those not familiar with the derby’s history. Even though time is tight here (owing, no doubt, to having to fit within an hour’s worth of TV time, with commercials), some good little tidbits of info are parceled out for fans, including the way TV instantly changed the game (the skaters immediately started to ham it up for the cameras), and how difficult it was for a player out on the road (one player switched to setting up the track—it paid double what he made as a relatively famous player).

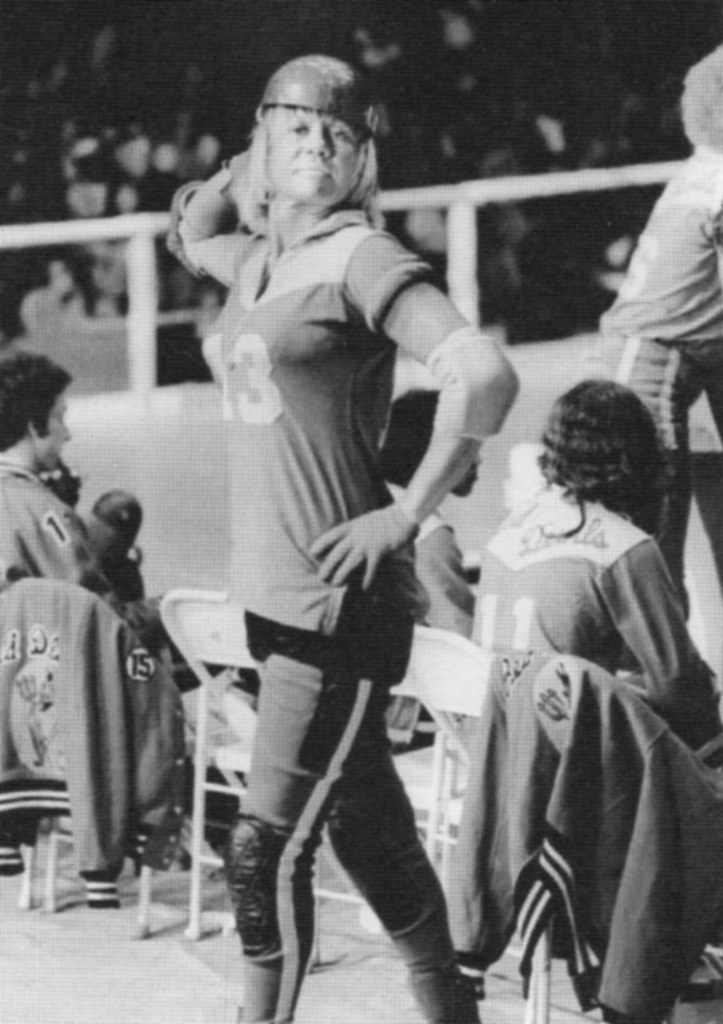

New interviews with greats such as Mike Garmon, Francine Cochu, and Gwen “Skinny Mini” Miller alternate with vintage looks at other superstars of the sport such as Joan Weston (“The Golden Amazon!”), Ann Calvello, and Mr. Roller Derby himself, Charlie O’Connell (why someone didn’t give that guy his own sports talk show, I’ll never know), with Rolling Thunder utilizing quite a bit of archival material to good advantage. Only towards the end of Rolling Thunder did I wish there was more time on the clock; the demise of the sport in the 70s, and the subsequent perversion of it into a pro-wrestling/circus-like entertainment via the Roller Games organization, are big themes in the sport’s history. But they’re rushed through here at the end with only a few spare minutes of screen time. Still, for a crash-course in the game and its historical context, Rolling Thunder is well done.

DERBY

Back in 1970, when roller derby was enjoying the absolute height of its second golden age, roller derby owner Jerry Seltzer commissioned this documentary on the sport, enlisting Robert Kaylor to photograph and direct it with, I would assume, the intent of further publicizing Seltzer’s business (unfortunately, the two commentary tracks that are available on the stand-alone DVD release of Derby—commentaries that apparently provided a wealth of information on the doc and its production—are not included on this set).

And you can see some of that footage here, as the filmmaker records derby greats like Ann Calvello and Charlie O’Connell discussing what the game means to them in terms that are quite revealing at times (O’Connell’s trip back to the New York City park where he first roller skated as a child is both sweet and sad), while also hitting the banked track with some energetic hand-held footage that shows what punishment these skaters took, even if the “fights” were mock (take a running jump on a hard wood floor and land on your ass…and then do it again and again about ten times in an hour…and then do it almost every night for nine months). We also get some glimpses into the relatively hard life the skaters lived out on the road (in comparison to other comparable sports stars of that era): little pay, no glamour, and not even the most basic necessity of a traveling sports team—a bus (the skaters actually drove themselves to the games all over the country).

All of that is quite interesting in that instantly recognizable grunge cinema verite style of Derby‘s. The camera stays close and rolls on; the available lighting is bad, the shots grainy, and the subjects are only observed…with commentary supplied later in the editing. The skaters aren’t made fun of (nor are they pitied or championed). Events are…recorded in these segments.

RELATED | More 1970s TV reviews

Where Derby really comes alive is when the documentary obviously abandons its mission—telling the story of 1970 roller derby for its owner and the doc’s producer, Jerry Seltzer—and becomes something much more in the telling of would-be roller derby skater Mike Snell’s story. Fairly early on in the doc, we’re treated to a blandly depressing locker-room peek at the players, complete with a ref zipping up after taking a leak. Suddenly, there’s a knock on the door, and in comes Mike Snell, a 25-year-old employee of the Dayton Tire and Rubber Company.

Conversing with a skeptical but polite Charlie O’Connell, Snell makes it clear: he’s quitting his job and moving to California to enroll in the roller derby training school for a chance—a chance—at trying out later for one of the teams. Snell has worked on the line for three years; his pay isn’t great, but he’s supporting his wife Christina, his two young children, his younger brother Butch, his parents…and a veritable bevy of girlfriends on the sly (you could do that with 1970 dollars).

Derby was a big hit with critics when it came out in 1971, many of whom responded to the doc’s impish fixation on the low-class hijinks of horn-dog Snell. But it struck a sour note with hard-core derby fans who wanted to see more of the game and the famous players and much, much less of Mike Snell and his family. As much as I enjoyed the Snell segments of Derby, I did find myself wanting to get a better understanding of the milieu that held such fascination for a guy like Snell.

Much of Derby focuses on Snell’s almost blasé certitude that he’ll better his life by becoming a derby skater, and it’s difficult to argue with that prediction when you see exactly what kind of life he leads. Predating Jerry Springer and Maury Povich by twenty years, the Snell saga involves dead-end factory jobs (Snell shows up for work when he shows up…and who can blame him), crummy, run-down houses, slack-jaw TV gorping as a substitute for wish fulfillment, assorted fringe friends, and the excitement—for both Mike and his wife—of his cheating around (having to confront one of Mike’s girlfriends—the doc’s best scene—Christina at least seems grateful for something different to do that day).

Add to that some genuinely strange, hilarious scenes involving Mike’s younger brother Butch, who lives down in the basement, reading Playboys and making deceptively wise-ass comments inbetween his avoiding doing the smallest task, and you have a potent little slice of crumbling (both economically and morally) lower-middle class America, circa 1971. However, to make the connection between Mike’s actual life, and what he dreams it will be, we should get a better look at his obsession: the derby. And that doesn’t happen in Derby.

There are a few scenes with derby superstar Charlie O’Connell—thoughtful, telling scenes where he discusses his childhood as well as his anticipated retirement—that are no less compelling than the Mike Snell scenes…but they come and then go as the Snell sequences dominate. O’Connell could easily have been the main subject of Derby, and perhaps viewers would have seen a more layered side of the game had the filmmakers stuck with this giant in the derby. Who can say? As it stands, though, it’s ironic (considering Seltzer’s original intention in commissioning it) that the thoroughly engaging Derby is much more likely to appeal to those viewers who normally wouldn’t be caught dead attending a roller derby tournament.

GAME FILMS AND TAPES

My favorite part of The Roller Derby Chronicles set: vintage game films and tapes. That’s right: vintage roller derby is back. I was pretty small, but I have distinct, wonderful memories of going to the derby at our local sports arenas back during the game’s slow death in the early 70s (had to have been Big Time Wrestling out of Detroit). Now, the old man knew just how to make the experience complete: he bought the tall cups of popcorn for us so that when my brothers and I were done eating, we could pop the waxed bottoms out and use the long cups as megaphones…and he let us scream our heads off (obscenities allowed, if he was smashed).

Think of the opening of Slap Shot, and you’ll get a picture-perfect visual reference for the old Toledo Sports Arena (long gone), or one of the filthy exhibition halls right around the corner from us at the Lucas County Rec Center (now minutes away from getting bulldozed). Dirty cinderblock walls and trash in all the corners, the loud buzzing of the yellowed florescent lights, the small, drunk, pissed-off crowds screaming for something to happen, and the past-it athletes turning round and round on their crappy little make-shift banked track. Jesus, that was a good show.

You kind of get that grungy feeling when watching some of the videotaped games from the 70s included here (I particularly like it when the camera tries to stay framed on just the few rows of seats that are occupied), but I really enjoyed the earlier filmed footage from the 50s, with the huge banked track and the powerful skaters who really emphasized form and athleticism over any kind of showboating (listen to the announcers playing up to the fans, 50s-style; one enthusiastic announcer details Charlie O’Connell’s stats, adding at the end, “…and he’s single!”).

Disc 2 of the set includes the second half of a 1959 match between the Chicago Westerners and the San Francisco Bay Bombers; the second half of a 1960 match between the New York Chiefs and San Francisco Bay Bombers; the second half of a 1974 match between the Los Angeles Thunderbirds and the Canadian All Stars; and periods seven and eight of a 1952 match between the New York Chiefs and the Jersey Jolters.

On Disc 3, two full derby games are included: 1973’s New York Chiefs versus the San Francisco Bay Bombers and 1977’s Brooklyn Red Devils (top of the food chain…) versus the San Francisco Bay Bombers. Baby, that is almost seven hours of vintage roller derby action on those two last discs. Jams are blocked. Fake punches are thrown to the head. Up and over the railing spikes occur with abandon. Fros are mussed. It’s…beautifully American in its utter sincerity and total shine-on b.s., and I for one miss it like mad.

Read more of Paul’s TV reviews here. Read Paul’s film reviews at our sister website, Movies & Drinks.

thank you for the article

LikeLike